Hi Jamie,

You’re definitely not the only maker out there who feels this way about fusible interfacing, because it’s one of those areas where things can go wrong very quickly.

We’re looking at interfacing this month as part of our Sewing Shirts Skills Kit project for Curated by ITF. Interfacing is an important component of shirt making (and garment sewing in general) and so it’s definitely timely that we answer this question for everyone.

WHAT IS INTERFACING?

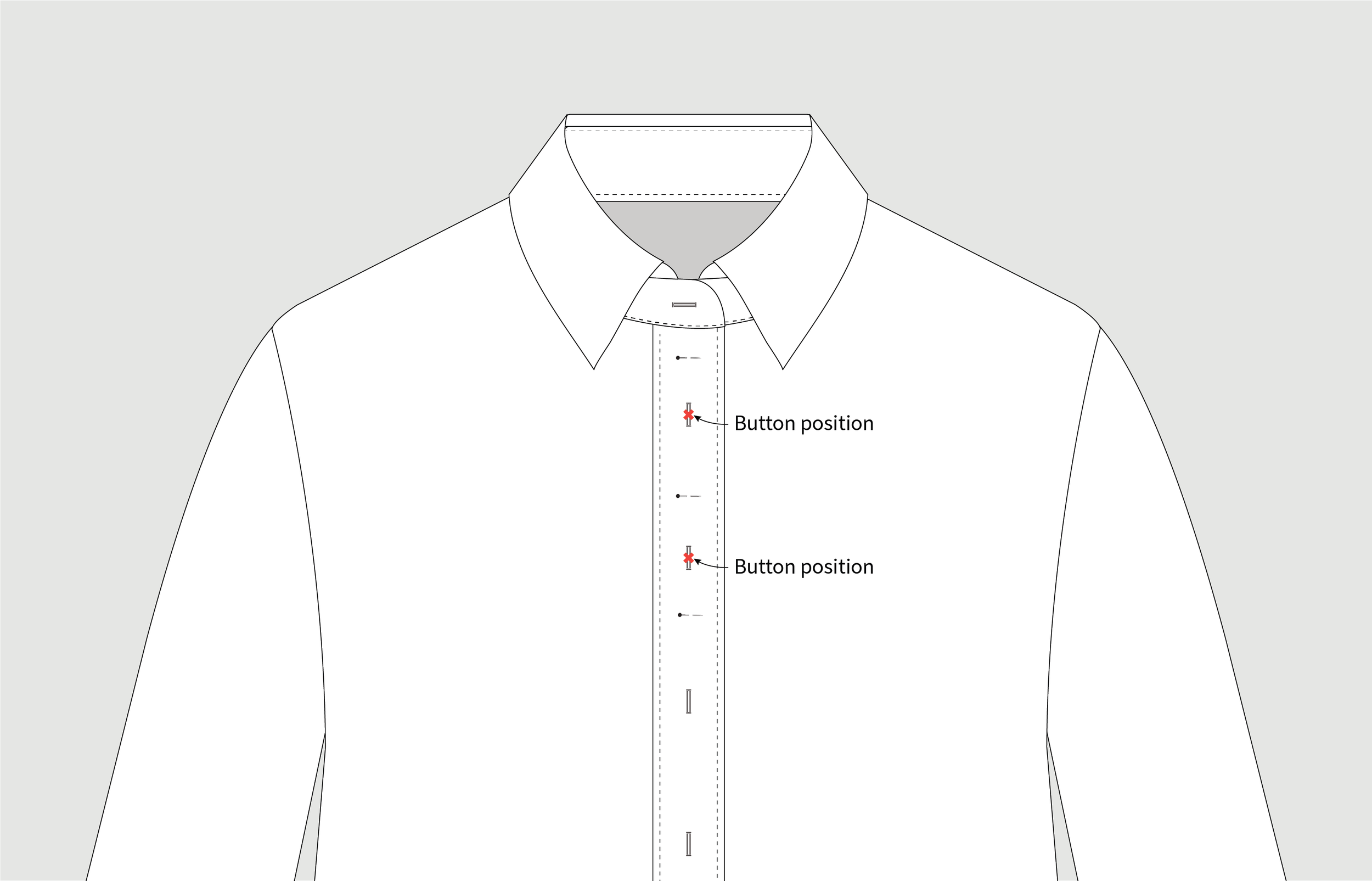

Interfacing is an additional layer that is applied to fabric to create structure in a garment. It is also used to ensure certain areas of a garment hold their shape or can support a particular part of a garment. Finally, it can be used to reinforce high stress areas of a garment (for example, buttons and buttonholes).

Interfacing is applied to the wrong side of the garment so is not visible once the garment is assembled. The most common parts of a garment to use interfacing are: collars, cuffs, button plackets and waistbands. But, it may also be used on facings or around pocket openings for extra support or reinforcement.

TYPES OF INTERFACING

There is a wide range of interfacing available, but generally there are two main types of interfacing that you would be aware of.

Iron-on (or fusible) interfacing

This has a thin layer of glue on one side and needs to be bonded with the fabric using an iron or fusing press.

Most garment makers would predominantly use fusible interfacing, however there are some applications where it isn’t appropriate, such as:

Fabric that can’t be ironed, such as sequins, anything with a nap (velvet or fur), vinyls or metallic fibres.

Very sheer fabrics

Anything with a loose or open weave (eg. mesh, lace)

Fabrics that are heavily textured as it may not bond well.

Sew-in (or non-fusible) interfacing

This type of interfacing is not bonded to the fabric, rather it is attached by sewing it to the fabric. It is most commonly used when you are using a fabric that cannot be pressed or has a texture that you would like to avoid pressing. Fabrics, such as stable cotton, can be used as sew-in interfacing and is something you can also experiment with!

Within these two main types, interfacing can be further categorised by the way it’s made:

Non-woven interfacing

Made by bonding the fibres together, non-woven interfacing has no grain and can be cut in any direction without fraying which makes it very easy to use. However, it can be quite delicate and tear easily, yet at the same time it can be quite stiff with a paper-like quality. For this reason, we believe it is better suited to craft projects and bag making.

If you’ve purchased interfacing before, it’s likely that you’ve purchased non-woven as it’s readily available and tends to be one of the cheaper options.

Woven interfacing

Constructed in the same way as woven fabric, woven interfacing behaves and moves like woven fabric, so it’s the best choice when working with woven fabric as it is less likely to affect its drape.

Like woven fabric, woven interfacing has a grainline so pieces need to be cut on grain (in relation to the grainline on the pattern). The benefit of woven interfacing is that it is able to move with the fabric, and is less likely to affect the drape and fall of a fabric.

Knit interfacing

Knit interfacing has some crosswise stretch and minimal lengthwise stretch so that it can add stability and support to knit fabric. Knit interfacing can be used on woven fabrics and can be a good option on lightweight fabrics that naturally stretch and have drape.

INTERFACING WEIGHTS

Interfacing also comes in multiple weights - light, medium and heavy. When choosing the weight of the interfacing, it is a good idea to select an interfacing that is the same weight or lighter than the fabric you are using. Lightweight woven interfacing will be most commonly used for garment sewing.

EXPERIMENTING WITH INTERFACING

Before selecting interfacing for a project, it is a good idea to experiment with different options on the fabric you plan on using.

We recommend you cut swatches of fabric (approximately 10cm x 10cm / 4in x 4in) and fuse the interfacing to the wrong side. Label each one with the interfacing you used. To compare, pin them to a noticeboard or onto a mannequin on one corner so you can see how they drape. Fold each piece in half and feel how it feels when it is doubled, as this is how it will feel on a collar or cuff (if you choose to fuse both sides of the collar or cuff).

TIPS FOR WORKING WITH IRON-ON INTERFACING

There is a lot of conflicting information out there about how to apply interfacing. Don’t use steam. Use LOTS of steam! Use a damp cloth. Don’t use a damp cloth…

Thankfully, there are places we can go to benefit from other people’s experience, like this interfacing focused Sewing Pattern Review thread.

We recommend that you start out following the manufacturer’s instructions, and then trouble-shoot if you’re still having problems.

Here’s a few tips!

Use high quality interfacing. The difference is noticeable!

For light coloured fabrics, use white interfacing. For dark coloured fabrics, use black or grey interfacing. It's handy to have some of each colour in your stash.

Prewash your fabric so that it doesn’t shrink when you fuse the interfacing with heat. This may be what is causing your interfacing to bubble as the fabric will shrink but the interfacing won’t.

Cover your ironing board with a large piece of scrap fabric or calico. This will protect it from the interfacing adhesive.

If piece fusing, sandwich the interfacing between two layers of paper and then cut out the pattern piece/s. This will ensure the interfacing does not stretch and the pieces are cut accurately.

Before fusing your interfacing, always check which is the right and wrong side. The right side is smooth and the wrong side (the side with the glue that attaches to your fabric) is bumpy. If you look closely you can see the small glue dots on the wrong side.

Cut the interfacing slightly smaller than the piece of fabric you are interfacing. This will prevent the interfacing going beyond the edges and ending up on your ironing board (or scrap fabric).

Start with your iron on a low setting and work your way up until the interfacing fuses to the fabric without burning.

Place the iron down onto the interfacing without dragging across the interfacing. Press to fuse one section and then lift the iron and put it back down on the next section. This will prevent the interfacing from stretching or moving into the incorrect position.

When the interfacing is fused to the fabric, turn the fabric to the right side and press (you can drag the iron across once the interfacing is attached).

Side note: We know that in the home sewing industry it is often recommended to use a damp press cloth when fusing interfacing to fabric. This approach is not used in the professional garment sewing industry and it isn’t the approach we use ourselves, but we recommend following the manufacturer’s instructions if that is what is advised.

I hope this helps, Jamie!

Happy sewing,

Emily