THE Q & A SERIES

GETTING STARTED WITH DELICATE FABRICS

If you’ve ever dreamt of sewing with silk, chiffon or organza but hesitated at the thought of slippery seams and fraying edges, you’re not alone. Delicate fabrics can feel intimidating at first, but with the right preparation and a little patience, they can be incredibly rewarding to sew.

The key is to slow down, set yourself up for success, and let the fabric guide you.

This guide brings together our favourite tips from the Delicate Fabrics Hack Kit and Skills Kit to help you begin your journey with confidence.

1. Know Your Fabric

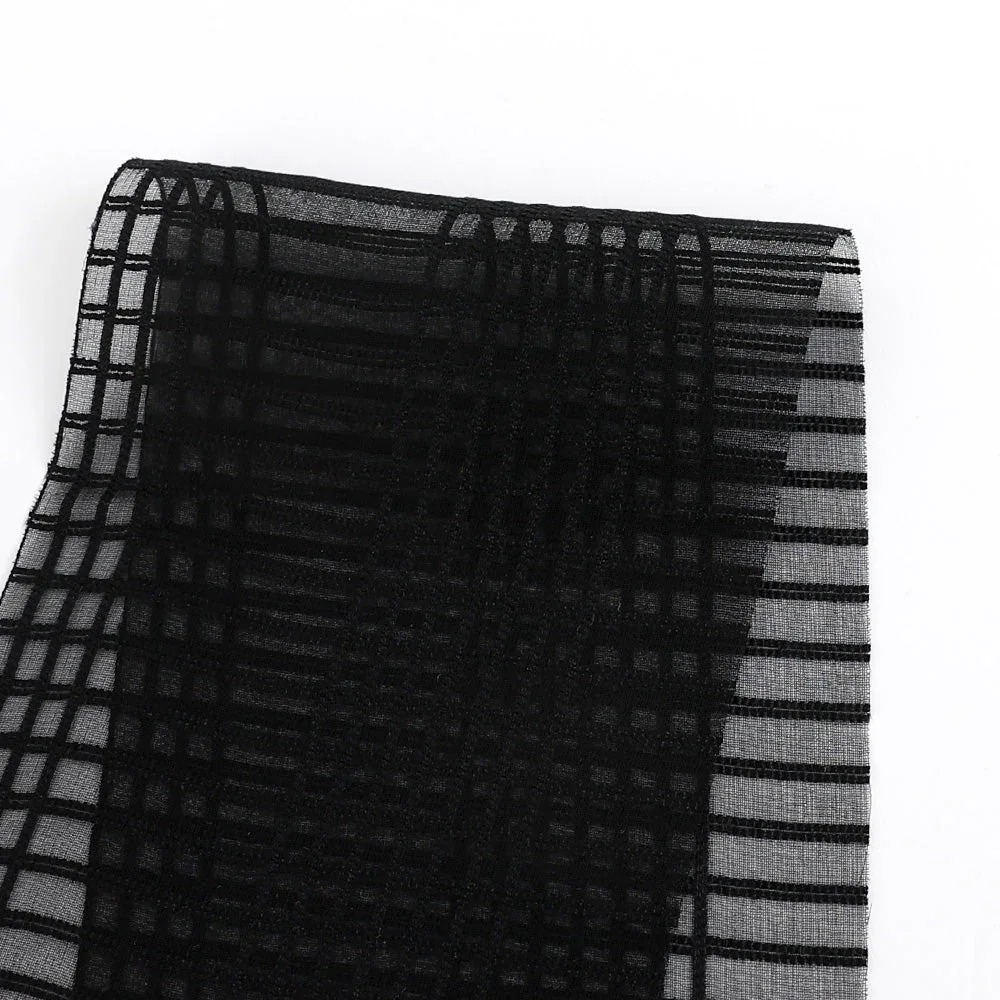

Each delicate fabric has its own personality. Silk charmeuse drapes like liquid and catches the light. Crepe de chine has a soft, matte texture and gentle crinkle. Organza is crisp and sheer, while georgette feels airy and slightly springy.

Before you cut, spend some time getting to know how your fabric moves. Hold it up to the light, notice its weight and transparency, and press a small test corner to see how it reacts to heat. Understanding these qualities will help you choose the right techniques and finishes later on.

2. Prepare Your Tools and Space

When working with fine fabrics, your tools can make all the difference.

Needles: Use a fine, sharp needle such as size 60/8 or 70/10 to avoid snags or visible holes.

Thread: Choose a high-quality polyester thread. For extra softness, try silk thread.

Pins: Fine silk pins or glass-head pins are best. Pattern weights help avoid marks.

Pressing cloth: Use a silk organza cloth to protect the fabric and see your work clearly.

Before you begin, clear your workspace and check that your cutting surface is smooth. Even a small nick or rough patch can catch on delicate fabric.

Clover Glass Head Silk Pins

3. Set Up Your Machine

Delicate fabrics prefer gentle machine settings. Always test on scraps first.

Stitch length: 1.5 to 2.5 mm.

Tension: Adjust to prevent puckering. If stitches look uneven, reduce presser foot pressure.

Machine feet: A Teflon foot helps fabric glide smoothly. A walking foot keeps layers even.

And when in doubt, hand baste. Slower, yes, but it gives you control and precision.

4. Prepare and Cut Carefully

Pre-wash your fabric gently, then give it a light press before cutting. Because delicate fabrics shift easily, stabilising is key.

Try these methods:

Cut in a single layer to prevent slippage.

Place tissue or pattern paper underneath and pin through both layers.

Use a rotary cutter with a sharp blade and pattern weights for clean edges.

Accuracy at this stage will make sewing far easier later.

5. Try Spray Starch

A light mist of spray starch can help keep slippery fabrics stable while cutting and sewing. Use sparingly and always test first, as too much can leave residue or stiffness.

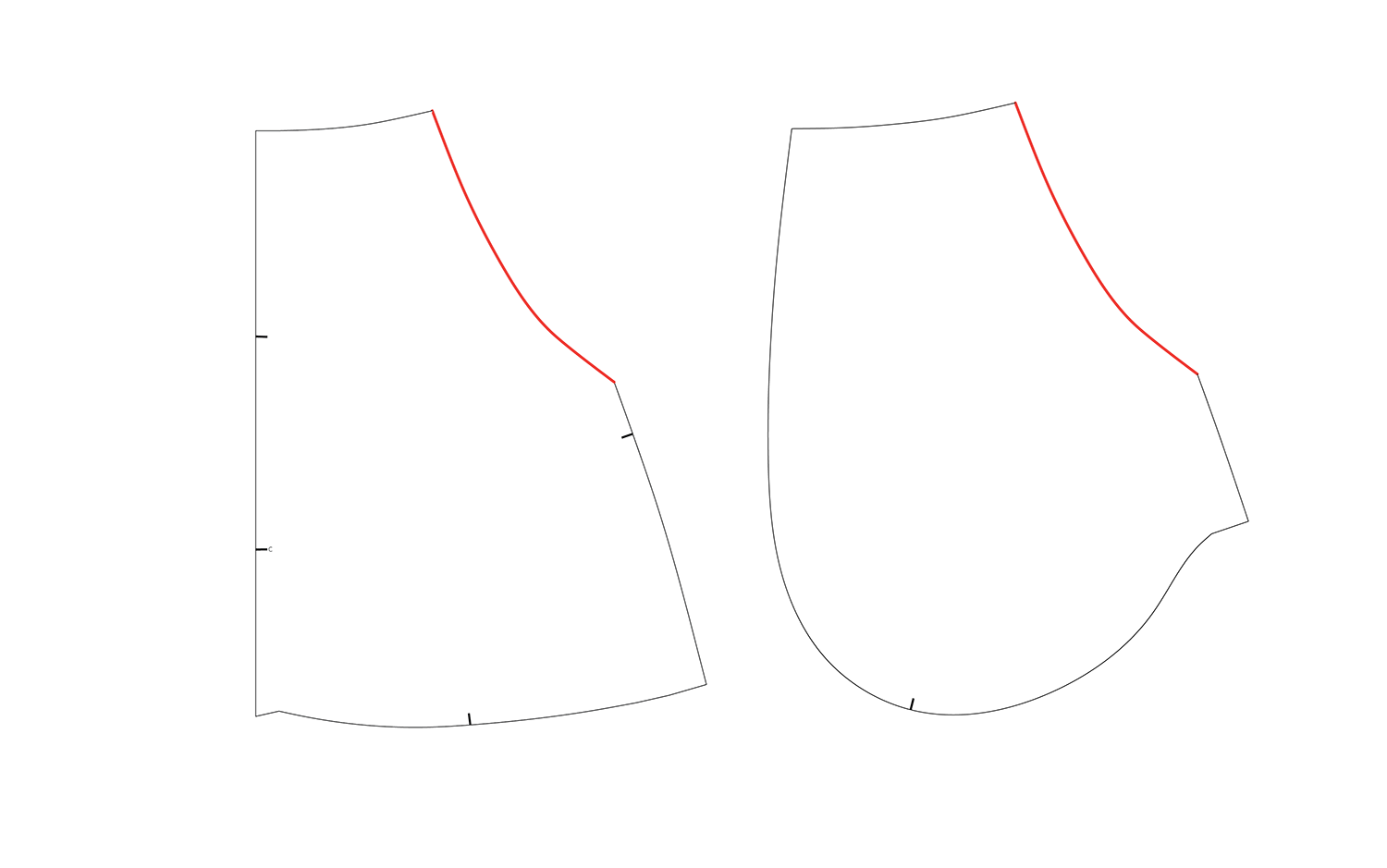

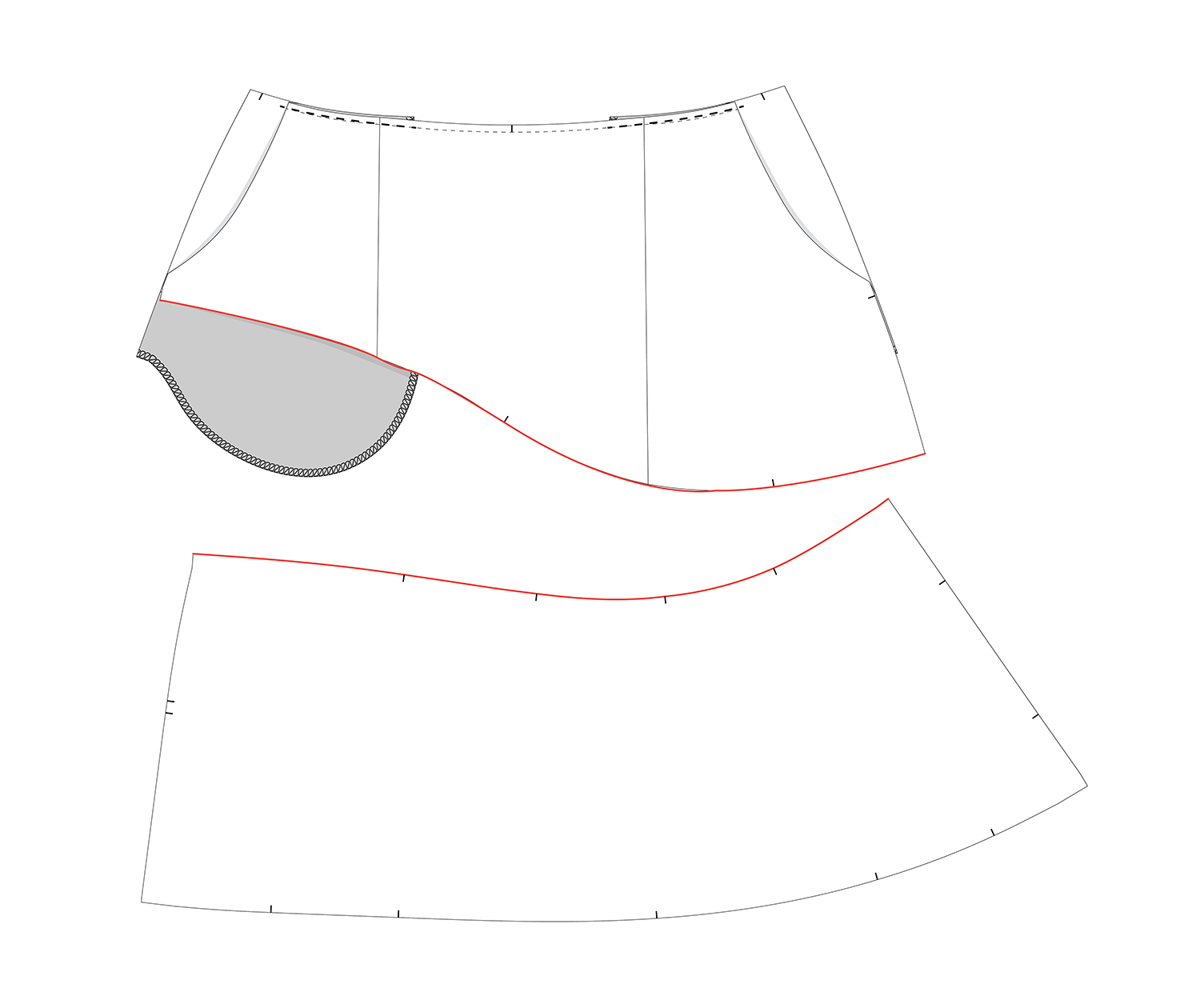

6. Choose the Right Techniques

Delicate fabrics shine when finished lightly and cleanly.

French seams enclose raw edges for a neat, refined finish.

Rolled hems add an airy drape to sleeves and edges.

Bias or French binding works beautifully for necklines or sheer edges.

Each finish should support the fabric, never overwhelm it.

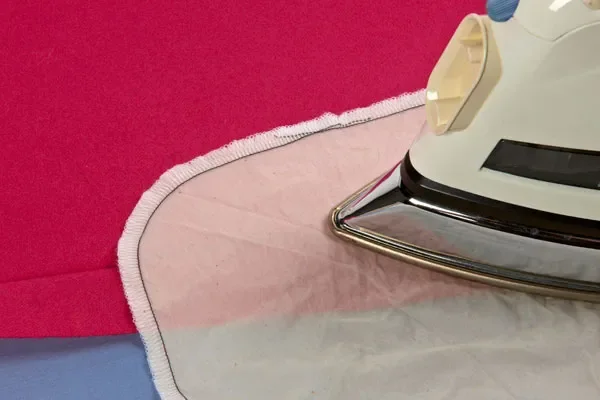

7. Press Thoughtfully

Pressing sets stitches and shapes your garment. With delicate fabrics, gentle is best.

Use steam carefully, always with a pressing cloth, and let each section cool before moving it. Think of pressing as sculpting the fabric into its final form.

8. Embrace the Process

Sewing with delicate fabrics invites you to slow down. It’s an exercise in patience and precision, but the results are worth it—the soft sheen, the fluid drape, the seams that melt into the fabric.

Start small with a sleeveless top or scarf and build your confidence. Each project teaches you something new about the balance between control and flow.

Ready to Try It?

Explore our Delicate Fabric Series in Curated for step-by-step tutorials on French seams, rolled hems and more. Each project is designed to help you learn at your own pace, one technique, one stitch, one beautiful fabric at a time.

RESOURCES MENTIONED IN THIS ISSUE

For more issues of the Q & A series, you can check out the archive here.